Catching MCAs at the Intersection of Infrastructure and Influence

Introduction

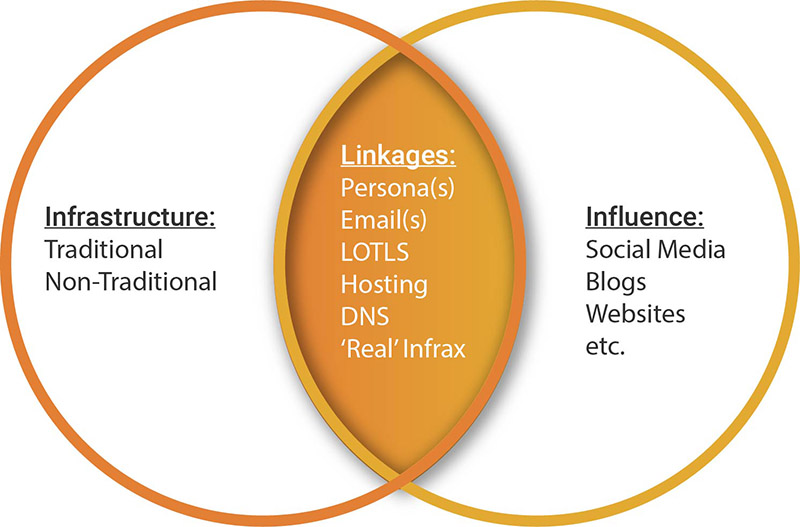

While most often associated with the Dark Web, the idea of relative anonymity on the internet is nothing new. It is easy for anyone to create a persona by setting up accounts on social media, email, blog sites, free forms sites, and other services using a fake name. Once these capabilities are in hand, the persona can set up a fan account for their favorite band or possibly create an anonymous blog to rant on the topic of the day. Do many legitimate, law-abiding citizens create fake accounts and profiles (sometimes termed “sock puppets”) regularly? Absolutely. Do Malicious Cyber Actors (MCA) do the same thing? They do, except that MCAs use their personas to procure infrastructure with the intent to deliver attacks against unsuspecting victims. Worse, MCAs utilize social media profiles to influence societies for both political and other nefarious purposes. Sometimes, MCAs use both infrastructure and influence to maximize desired effects. When that happens, linkages may become discoverable to aid cyber defenders in catching MCAs, as well as allowing cyber defenders to identify and block potentially malicious activities, protecting their organizations from harm. This post looks at the intersection of infrastructure and influence to provide analysts with an overview of the challenges in this area of cyber defense.

MCA Infrastructure

In general, today’s MCAs utilize two types of infrastructure, traditional and non-traditional. The zvelo Cybersecurity Team encounters both regularly, and it is important to define each type for common understanding.

Traditional MCA Infrastructure

Traditional MCA infrastructure includes those things needed for a presence to work on the internet. This includes registered domain names and DNS records, website hosting services, use of legitimate items such as Secure Socket Layer/Transport Layer Security (SSL/TLS) certificates, email addresses, and even Virtual Private Networks and Proxies. MCAs utilize traditional infrastructure in an attempt to appear legitimate on the internet. Sometimes in their haste, however, MCAs inadvertently provide clues about their activities by using traditional infrastructure. It probably comes as no surprise that MCAs do not use the most reputable domain name resellers or hosting providers. They take advantage of ‘trial periods’ offered by SSL/TLS providers thus, short-lived certificates always raise suspicion. High-entropy and randomly generated emails using the usual service providers (e.g., Gmail, Yahoo, others) are other indicators. If an MCA is sloppy, they will use the same email address for multiple traditional infrastructure transactions, leaving a trail of breadcrumbs that is easy to follow.

Non-Traditional MCA Infrastructure

Non-traditional MCA infrastructure is broken into three areas:

- Living Off The Land at Scale

- Kits and Services

- Social Media Personas

Living Off The Land at Scale

The first is Living Off The Land at Scale (LOTLS), a topic covered previously by the zvelo Cybersecurity Team. This MCA Tactic, Technique, and Procedure (TTP), includes using free forms and well-known/white-listed sites (e.g., Dropbox, Google Drive, others) to host malicious content. Another piece of this TTP, is exploiting unpatched and broken web-parts (e.g., WordPress) — again, hosting malicious content unbeknownst to the victim organization. Recently, the zvelo Cybersecurity Team observed MCAs using the PacketWhispher technique which creates random subdomain Fully Qualified Domain Names (FQDN) to avoid DNS caching and the requirement to actually register in the traditional sense. While part of the TTP leverages free services, it doesn’t necessarily mean that MCAs are utilizing those (e.g., DuckDNS) to implement their Command and Control (C2) channels supported by (Sub) Domain Generation Algorithms (DGA).

Kits and Services

The second part of non-traditional infrastructure is kits and services. In this case, MCAs purchase phishing kits or exploit kits to speed up the implementation of their nefarious activities. MCA time is “valuable” and someone else has already built a ready-made solution, so why not buy it? Related, MCAs (especially those with lesser skills) make use of online capabilities such as Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) to achieve their aims. Cybercrime Magazine points to the damage caused by ransomware reaching upwards of $20 billion by 2021 around the globe. And 2020 was certainly a banner year for ransomware with continued attacks on healthcare organizations, local governments, schools, and the list goes on.

Social Media Personas

Finally, the last non-traditional infrastructure piece of the MCA arsenal is social media personas. As social media platforms allow relative anonymity, MCAs utilize this capability to create followership and apparent legitimacy. Once established, MCAs then use this credibility to herd victims to both traditional and non-traditional infrastructure. Increasingly common, is the use of email-based personas to conduct phishing and spear phishing campaigns based on information gathered from social media snooping. Leveraging their deep knowledge of social engineering, MCAs are making easy money by preying upon just about anyone with an email address. Users who lack threat awareness training are easy targets as they are less discerning about clicking on whatever links may come their way.

The Cost Challenge for Cyber Defense

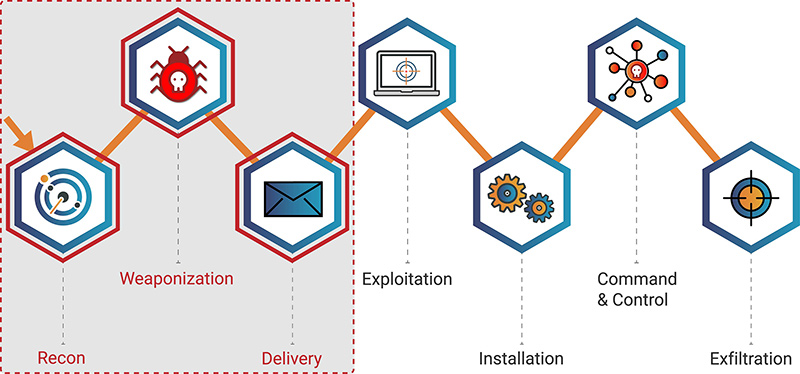

Facing savvy MCAs, a big challenge for cyber defenders is cost. The vast majority of the traditional and non-traditional infrastructure options the MCAs use are either free, or very low cost (sometimes offering “free-trials” which are used to great effect). Defenders, on the other hand, often expend significant capital when compared to MCAs, and breaches continue to happen at a breakneck pace. Looking at the Cyber Kill Chain (figure 1), you see that when MCAs effectively minimize their infrastructure costs, they maximize their Return On Investment (ROI), enabling them to invest those profits back into kits and services created specifically to automate more attacks. This makes it very difficult and incredibly expensive for cyber defenders to catch up, let alone get ahead of the MCAs.

One of the key non-traditional infrastructure pieces that MCAs use heavily are social media platforms. From Facebook, to Twitter, to Instagram, to LinkedIn, to TikTok, and beyond (WeChat, Telegram, and many more), it is incredibly easy to establish a believable online persona. Once established, these personas are used to generate a following and credibility. This was done to great effect in the 2016 US Elections at large scale by the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA). Now, that’s not to say the use of suspect online personas on social media is only the domain of nation states. It is, however, a known tactic they use very effectively.

But why? What makes this so easy? Simple — social media platforms value their customers (their revenue generators) and allow for the establishment of relatively anonymous accounts. In cases where an email or phone number are required for verification, burner accounts or global numbers are but a web browser search away. The savvier MCAs will avoid creating accounts or phone numbers that can be traced back to them. More on that shortly.

The next question of importance is why create a fake persona at all? That answer should be obvious. No-one is going to follow a nation state associated troll farm if they are out in the open. So, MCAs cloak themselves in trustable, likeable, and believable personas that fit into the groups they are looking to influence. MCAs in this mix include nation states, cyber criminal elements, terrorists, and even homegrown conspiracy theorists. Frankly, anyone can join the influence bandwagon, and many do.

The 2020 elections provided a superb example of an influence attempt where Iranian APT actors used stolen voter registration data and co-opted infrastructure to send threatening emails to voters. In this case, the personas were assumed by the MCA, but ultimately burned due sloppy execution. Given the existing concerns surrounding the elections, this type of activity could have been extremely damaging had the MCAs not been exposed. What is interesting in this case, is that it shows how influence operations (emails sent to intimidate votes) enabled defenders to uncover the infrastructure the MCAs used. The Iranian APT made use of infrastructure they had previously leveraged in other activities, and posted links to fake videos on various social media platforms including Facebook and Twitter.

The moral of this part of the story is be wary about online content. If something seems too good to be true, it probably is. If someone joins your social media circle that you do not really know, or who seems to be stoking the fire for no obvious reason, step back and look at the bigger picture. Most importantly, never click on a link (especially shortened ones) that you receive via direct message, text, or email if you are not certain of the origin.

The Intersections of Infrastructure & Influence

There are often linkages between infrastructure and influence that help cyber defenders in catching MCAs. When an MCA establishes a persona, it is usually not just for social media activities. Personas are created to have the look and feel of a real individual and, making them credible takes quite a bit of time and effort. As such, these personas set up emails and social media accounts to interact with the world. They purchase domain names and hosting space to establish a history of online activities, with the hopes their persona will pass for just another citizen of the web.

Once a persona is established as credible, MCAs use it to execute LOTLS TTPs taking advantage of free or next to free online services. Traditional infrastructure may be purchased to support MCA aims. One obvious give away when assessing whether infrastructure is real or not, is the DNS mapping. There are multiple tools that can be used to map out DNS records. The zvelo Cybersecurity Team regularly observes and maps domains and subdomains that have no physical infrastructure behind them. For example, it is not uncommon to see an ftp[.]domainname[.]tld record associated with malicious or phishing campaigns targeting specific organizations or brands. The reason this stands out is that while File Transfer Protocol (FTP) is surprisingly still used despite the security risks, it is rarely associated with legitimate organizations that have a large presence on the web.

Sometimes, MCA personas are used to create the “real” infrastructure. Perhaps an MCA needs to host an actual C2 server based on the way their malware beacons function. This usually happens when the MCA is less experienced with more advanced techniques, such as DGAs. When a persona is used to acquire traditional or non-traditional infrastructure, the ability to hunt back to the source increases exponentially. It is key to point out that MCAs are not doing some dark arts magic when acquiring infrastructure. They follow the same internet standards as everyone else, but likely procure their items from providers with lower ethical and verification standards. It also helps when MCAs are sloppy, as assessed by the zvelo Cybersecurity Team. In one instance, the MCAs created multiple fake DNS registrations, all of which mapped to the same IP address using a tech stack that was nothing like the spoofed site. In other words, don’t spin up Windows IIS and try to pass it off as legitimate when the site the MCA scraped is built using Linux and Apache.

Influence linkages are tougher to discover, but they are certainly there. Obviously, a purpose-built social media persona is not going to be the easiest to uncover. However, social media personas can be found to herd their followers to real infrastructure. Perhaps it is a simple link to check out a video as seen in the Iranian APT example. The video was uploaded by a person somewhere. Things do not just appear on the internet, someone had to take an action to put an artifact onto a site or service. This is where things begin to unravel for the MCAs. Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) analysts are on the lookout for these clues, piecing together the mystery to unmask and catch MCAs. In many cases, it takes time and patience when tailing social media personas, but the effort often proves worthwhile.

Models for Finding the Intersections

Analysts can use multiple models to identify the intersections of infrastructure and influence which can aid them in catching MCAs. When it comes to infrastructure, the Cyber Kill Chain is a good starting point. Specifically, the first three phases of this model (Recon, Weaponization, and Delivery) come into sharp focus as this is potentially where MCAs expose themselves procuring infrastructure.

Next, the MITRE ATT&CK models allows us to more closely examine the techniques MCAs are using in infrastructure deployments including:

- TA0042: Resource Development: https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0042/

- T1556: Phishing (https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1566/)

- T1190: Exploit Public-Facing Application (https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1190/

- T1199: Trusted Relationship (https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1199/)

In each of these techniques, MCAs and/or their personas create the artifacts needed to catch them in the act.

The last model of note is MITRE Shield. This maps the persona side of influence that can potentially be tied to infrastructure. The areas encompassed in MITRE Shield include items such as: Decoy Account, Decoy Content, Decoy Person, Decoy System, and so forth. This model recognizes that not everything on the internet is legitimate or trustworthy.

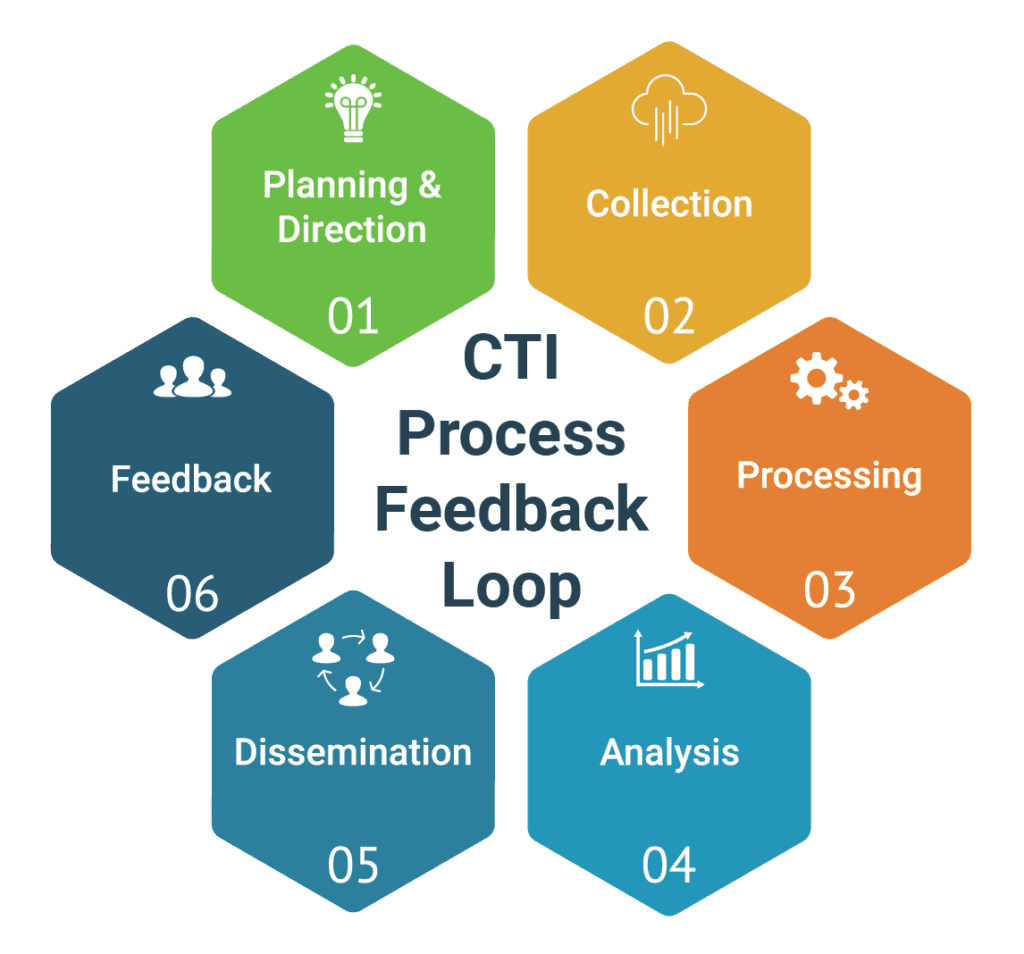

Now that the TTPs of infrastructure tied to influence are better understood, a logical question to ask is: How do you capture MCA infrastructure and personas to assess the linkages? The answer is to utilize the Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) as shown below:

With the CTI loop, cyber defenders can continually collect, analyze, and tune their hypotheses to understand MCA activities. Organizations and their networks function as organic entities so it is important to remember that CTI is a continual process which requires regular adjustments. For example, the zvelo Cybersecurity Team is constantly evolving their view of the MCA landscape to catch the latest/greatest campaigns and attacks. Organizations that successfully implement CTI to understand the MCA infrastructure and influence used against them, are better protected in the long term.

More Resources:

As an additional resource on this topic, we would like to include the link to a recorded webinar through the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

February 25, 2021 | CISA Webinar: Combating Online Influence and Manipulation.